Gay weddings are back. Well, back in court. This week, SCOTUS began hearing oral arguments for 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis. The case centers around Lorie Smith, a devout Christian who wants to expand her business to include wedding websites. Colorado’s Anti-Discrimination Act (CADA) prohibits businesses from discriminating against LGBTQ customers, which means Smith would be required to create invitations and other assets for gay couples despite her religious objection that marriage “is only between one man and one woman.” She is challenging the law on the grounds that it violates her First Amendment rights. SCOTUS refused to hear arguments rooted in the religious expression clause, but is considering the merit of her case under freedom of speech.

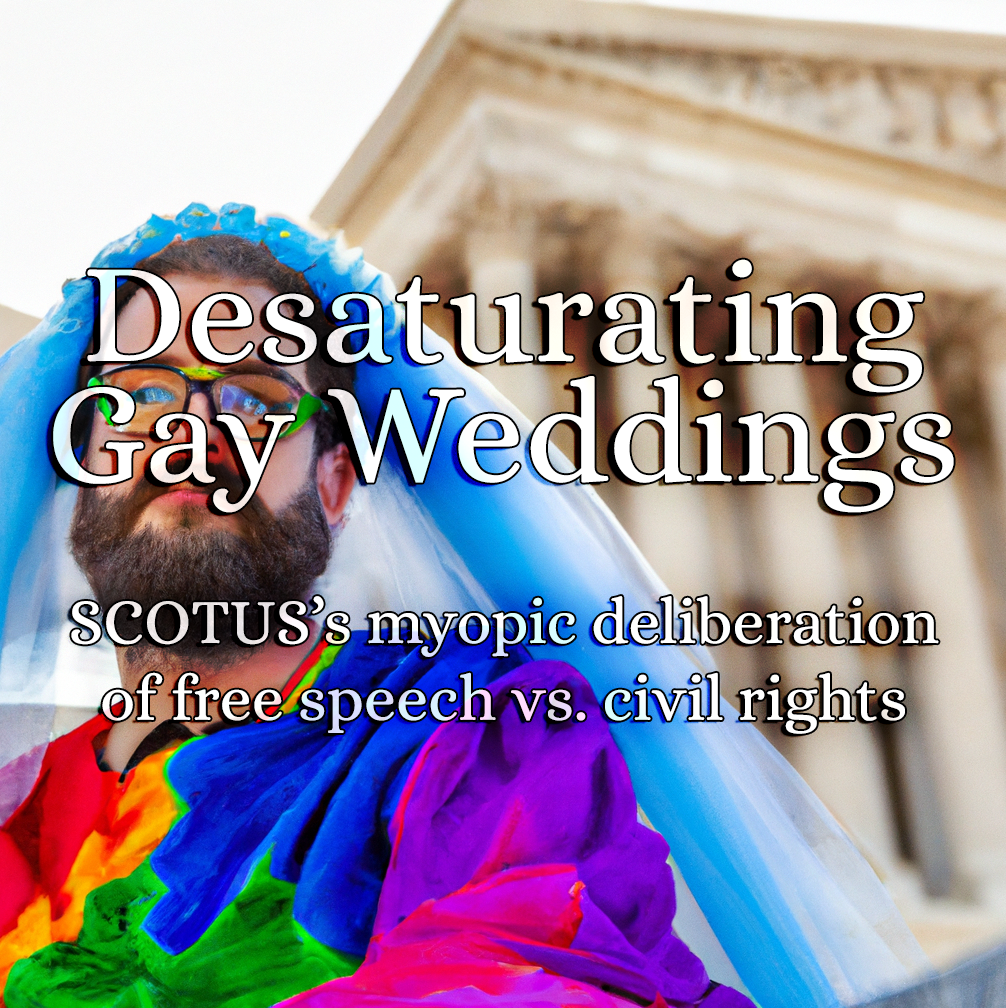

At issue is the question of whether forcing Smith to serve gay customers is a form of compelled speech. Smith argues that CADA would require her to create messages that undermine her religious beliefs. The prevailing supposition, shared by Justices, lawyers, advocates, and onlookers, is that this case is about striking a delicate balance of compromise between conflicting rights. Citing previous SCOTUS decisions, for example, an amicus brief filed by First Amendment scholars pits “the constitutional right to free expression” against “the exercise of their [homosexuals’] civil rights.” In oral arguments, Justices have been exploring the definition of “speech,” concocting various hypotheticals so they could contemplate whether the government should compel Jewish photographers to take profile pics for AshleyMadison.com or mall photographers to snap surreal shots of Black Santa Clauses posing with children draped in KKK attire. One line of reasoning is that photographers, painters, and website designers are expressing speech, while limo drivers, caterers, and bakers are not. Some chefs would undoubtedly disagree. There’s a clear tension in the air between two opposing sets of “rights,” and listening to the Justices “debate” leaves one with the impression that judicial arguments depend on the speaker’s preferred outcome rather than the other way around.

It’s an intractable problem because instead of anchoring the discussion in a clear philosophical concept of rights, the Justices are drifting in a fog, groping at a gelatinous bundle of imposter concepts passing themselves off as the real thing. Philosophically, rights are forms of prohibition, not entitlement: they don’t define what you must do, they proscribe what others must not do to you. The right to property is a prohibition on stealing, not a voucher for an iPhone, Internet service, or a house in Malibu. The right to life is a prohibition on murder, not a coupon for free meals. The right to free speech is a prohibition on using force to control your communications, either by silencing you or requiring that you speak, not a promise of a book deal from a publisher. Rights don’t compel any positive action from anyone, whereas entitlements always compel someone to action, since iPhones, Internet service, and houses in Malibu aren’t products of nature that the Universe magically provides, but products of the conscious labor of individual humans. Philosophically, rights can’t contradict one another. Contradictions only arise when other concepts–like entitlements–are allowed to masquerade as rights and poison the concept itself. To undermine otherwise decent laws, progressives need not alter one jot or tiddle of the Constitution itself; they need only control the dictionary.

Conflating rights with entitlements is a surprisingly easy mistake to make for people who want to fight injustice. We see a bigoted shop owner mistreat someone based on his race or perceived sexual orientation, and it angers us. We want the shop owner to behave better, but without turning to government, we have limited options: chastise him, organize a boycott, convince others to disinvite him from community events, etc. None of these guarantee that he’ll change his unjust behavior, so in a short-sighted fury many of us turn to the tempting promise of a government solution. The government can use violence to solve the problem; it can stick a gun in the shop keeper’s face and make him behave. We may not admit this violence lust to ourselves, but deep down we know it’s there; the very cornerstone of our strategy is to leverage the government’s monopoly on the use of force in order to control behavior. But it’s for a good cause, so we invent anti-concepts like the “right to not be discriminated against,” empower the government to guarantee that newly fabricated right, and bathe in the warm tide of moral adulation that follows. We’re so good. So noble. The world is lucky to have crusaders like us.

Substituting our messy, laborious, imperfect responsibility to persuade with a simple government responsibility to enforce may seem tidy and efficient, but it comes with a deadly price tag. Few notice the philosophical pathogen introduced by our actions, and even those who do often justify it by calling it “pragmatic,” as if ignoring long-term consequences is the practical thing to do. But that pathogen is necrotic. Over decades and generations it multiplies and corrodes, ultimately clouding our ability to tell the difference between morality and legality.

Eventually the year 2022 arrives, and the highest court in the land is arguing about what kind of photography counts as “speech.” Everyone in the room has long accepted the necessarily vague idea of “civil rights” and the government’s consequent responsibility to protect them. But they are also staring at a constitution that has something to say about “the freedom of speech.” These concepts are incompatible, but to modern thinkers they are also axiomatic, and a conundrum ensues. Conservative-leaning Justices seek to invent some philosophical distinction between website services as “art” and catering as “not art” so they can rule in favor of free speech without having to look too closely at so-called “civil rights.” Until Smith starts a catering business, that is. Left-leaning Justices use Nazi-era voodoo to conjure boogeymen for support: will website designers be able to refuse to service interracial couples, or the disabled? Justice Sotomayor is concerned.

The court is poised to rule in favor of Smith, striking down CADA in certain narrow cases, but we likely won’t see a verdict until early next year. In the meantime, Justices will debate about different kinds of web services, how much or how little a web designer is expressing herself in one instance as opposed to another, how much endorsement is implied in making wedding invitations, and the extent to which reusing copy undermines your expression claim. Yawn. The longer we all evade reality’s interdiction against contradictory concepts, the more consequential our arguments over minutia will become.

At this rate, expect a decision based on font choice to someday be the SCOTUS ruling that finally destroys us all.